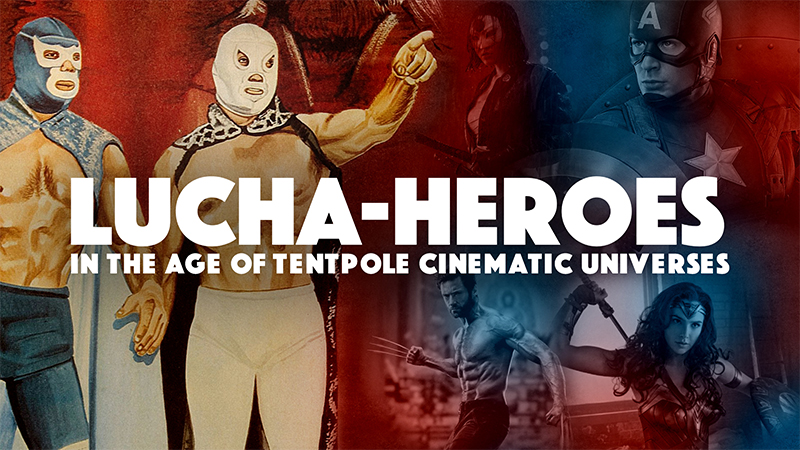

In August, at the 5th annual Latino Comix Expo in Long Beach, I sat down with a superb array creative types to talk about our beloved lucha-heroes and where they stand in this current era of mega-budget big studio superhero cinema proliferation. Following are the visuals from my introductory slide presentation along with text based on my speaking notes, followed by a list of the other creators on hand and where to find their work.

We started by remarking on the age we live in now, an age many of us long-time comic fans never thought we’d see — Justice League and Avengers competing films, epic superhero movies with even more epic budgets evolving from pipe dream to the norm to almost being too much.

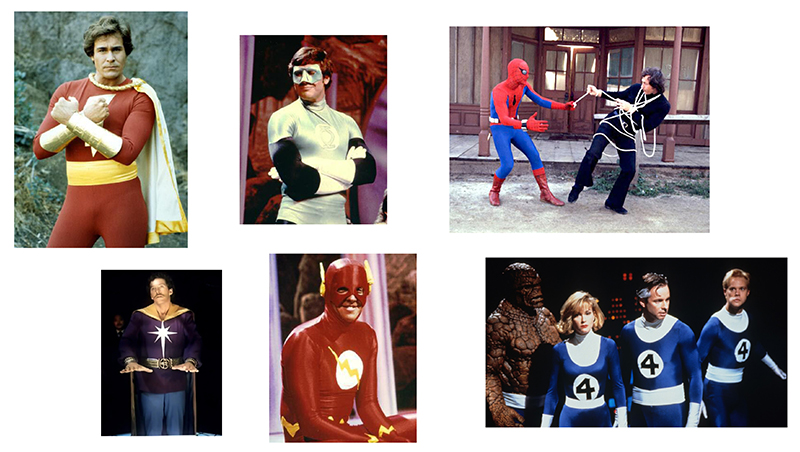

The crux of the discussion centered on costuming. Regardless of how much you like or hate a superhero film now, you can’t fault the costuming. Costumes are detailed, credible, look functional — crafted of astounding textiles and materials that make possible what was in previous decades somewhat underwhelming, or outright laughable.

When you consider that these costumes were either the best Hollywood could create, or the best they were willing to invest time, money and innovation in, it’s no wonder kids who grew up in the 60s, 70s and 80s are now adults positively floored by what’s being put on screen today. This array of vintage TV and movie costumes illustrates exactly how little was thought of the genre.

In Japan, both character design and costumes were taken a lot more seriously and executed on a level above. However one thing was missing from all the ‘transforming hero’ shows — a connection to the actor in the suit. Total head-covering designs basically meant stuntmen were in the suits instead of the actors audiences connected to in the non-costumed scenes. So once the hero transformation occurred there was no real acting, no emotion, no human connection.

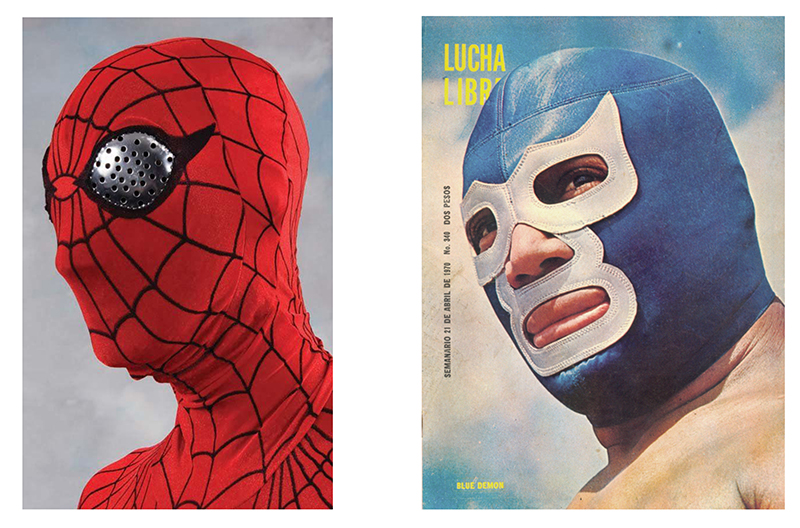

While this on the left was the best we could do here with superhero costuming, in Mexico they took a different route. With a dramatically different result!

Poorly executed superhero costuming elsewhere in the world produced garments often unfaithful to the original property by lack of means. They came off as cheesy at best, at worst, dangerous to the performers wearing them or the stuntmen working in tandem.

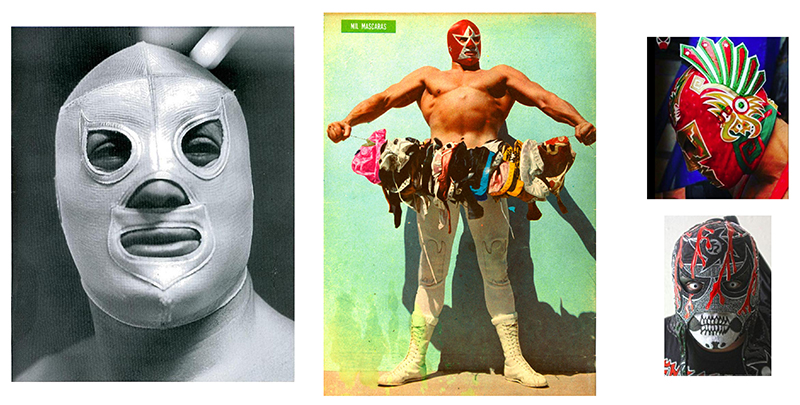

Meanwhile, the simple 4-panel, face-plated lucha libre mask in Mexico was all things other countries’ hero costuming wasn’t — credible to a 100% degree. These masks, tights and capes were literally combat-proven and battle-tested. The masks afforded the wearer anonymity under a distinct color and graphic scheme that allowed flashy character identity. At the same time they also afforded full vision, didn’t impair breathing and even offered a degree of protection. And audiences could still connect to the performer underneath — read their eyes, see them speak, get a facial expression of rage, fear, victory.

The simple choice of using wrestling masks for superhero garb, and wrestlers as superheroes, made the lucha-hero genre the most credible and realistic execution of the costumed crimefighter anywhere. American costuming wouldn’t catch up in terms of form and function for decades.

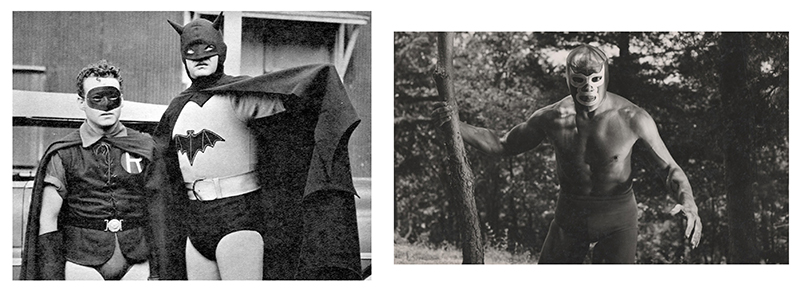

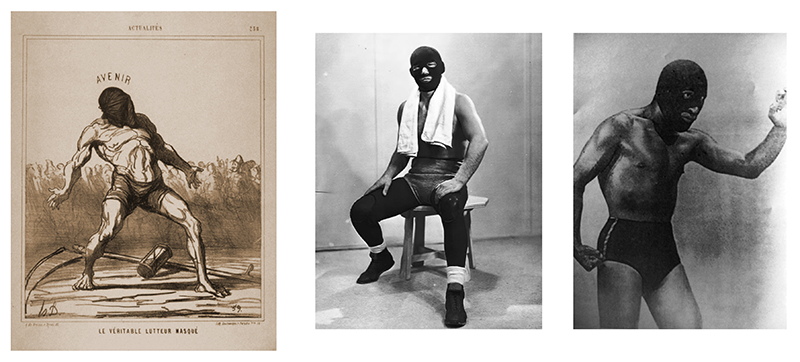

The wrestling mask didn’t originate in Mexico — hooded wrestlers appears in French grappling tournaments in the 1870s, various ‘Masked Marvels’ worked in the U.S. and Canada in the 1910s, and Mexico’s first enmascarado was a Texan — but it sure was perfected there.

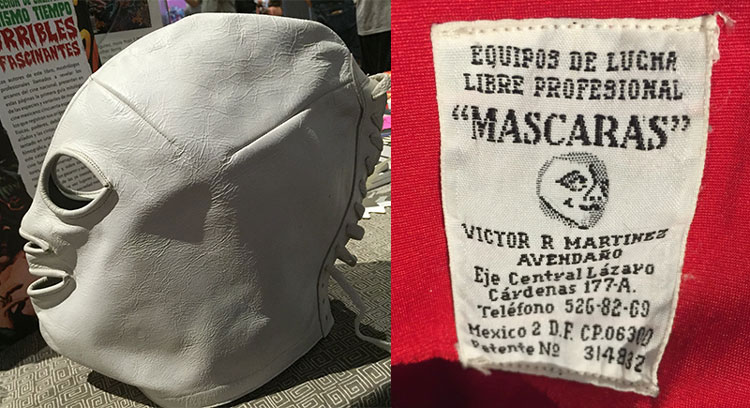

This is a souvenir version Deportes Martinez, now Mexico City’s longest running hood merchant, sells of their first mask from the late 30s. The original would have been goatskin I was told, and I just cannot imagine wrestling in that in an un-air conditioned Mexico City arena back then. Ugh…

By the 1940s, when American masked men were more often than not improvising their head gear from ski masks, women’s girdles and makeshift wool sacks, pioneering mask makers like Martinez were perfecting the science of the 4-panel design and combining flexible fabrics with rugged leather faceplates. When stars like El Santo and Blue Demon became the rage, simpler, largely monochrome masks made it easy for fans in even the cheapest seats to ‘read’ who was in the ring from a distance. In the 60s, color TV broadcasts and better printing methods of magazines gave a new canvas to innovators like Valente Perez and the envelope of mask design was blown open with the likes of Mil Mascaras. The trade never looked back, and today artists in Mexico and Japan are pushing the limits of what once looked like regulation protective gear but now knows no limits.

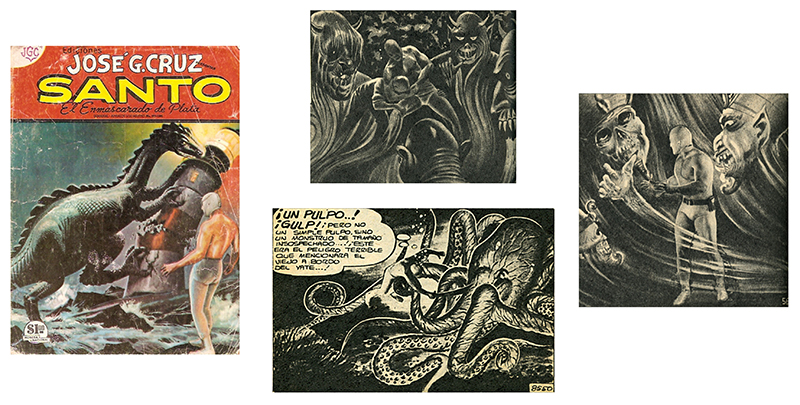

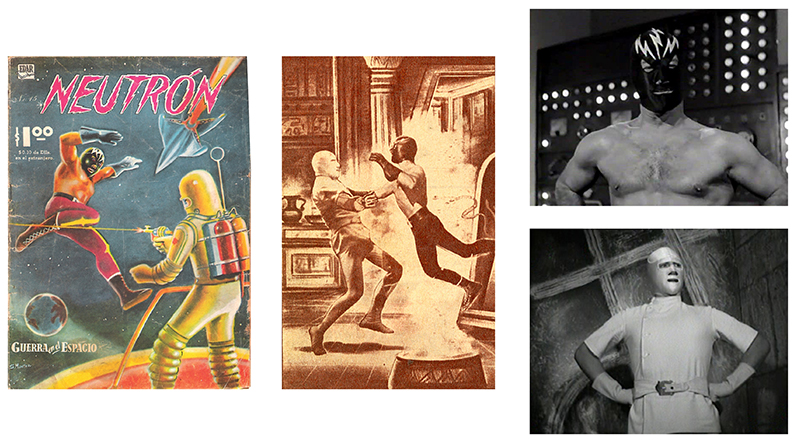

Mexico’s pioneering superhero filmmakers turned to wrestling gear for their costuming. These black & white Republic Serial-like adventures featured larger than life heroes like La Sombra Vengadora and Neutrón (known in English dubbed prints as “The Atomic Powered Super Man”), that while played by performers with some wrestling training were not actually wrestler characters.

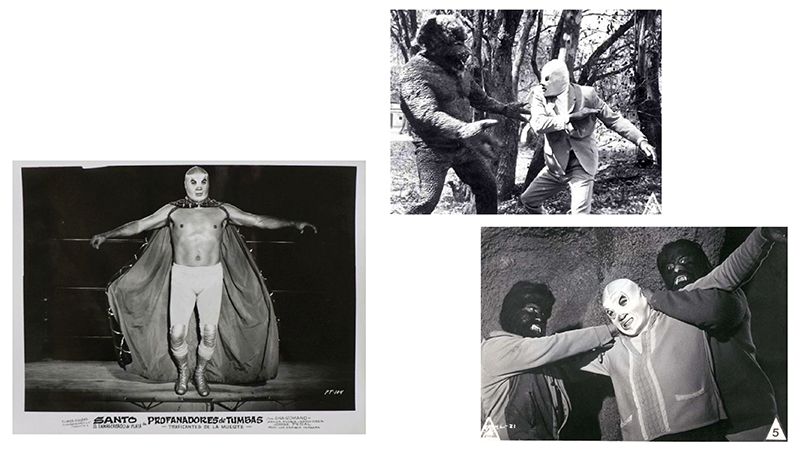

That natural (to us at least) leap was made when stars like Huracan Ramirez and El Santo started moonlighting as justice-bringers and monster-fighters. Famous enmascarados were a great deal for exploitation film studios — they brought their own fame, literally brought their own costumes, did their own fights and often stunts, provided a pool of wrestling friends to portray thugs and creatures of the night, AND every time one of these masked heroes entered the ring they were in effect doing free publicity for the films.

So enmascarados were ‘turkey-baster-ed’ into every and any conceivable film genre that could contain them — crime drama, horror, sci-fi, spy, slapstick comedy, even Westerns. The hoods fought foreign invaders, alien invaders, giant robots, giant blobs, seductive vampire women and somewhat less-alluring wolf-women, mummies, zombies and more.

The films enjoyed two decades of proliferation in Spanish-language cinemas all over the Latin world and North America, and distribution in Europe as well. The advent of cable, VHS and eventually DVD led to a growing international cult of fandom for the material, too. These films have aged very well and are better received than ever by generations of new cult film fans.

But what most of those fans don’t realize is all the conventions and tropes of the genre — the wrestler living a hooded life and moonlighting as a crime-fighter, the liaison figure with local law enforcement like a professor or cop sidekick, a hot babe on the arm and a cape flowing over the back of a two-seater Euro convertible, etc. — were actually cemented in comic books well before the silver screen.

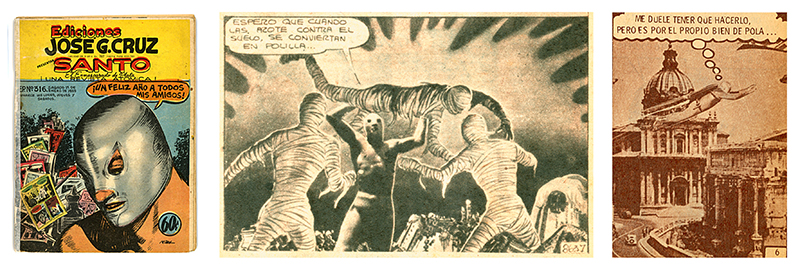

Sepia-toned ‘Revista Atomicas‘ (square-format comics digests on cheap newsprint) starring El Santo turned already successful artist and publisher Jose G. Cruz into a pulp magnate. At their height, these adventure books were being released as many as three times per week, with print runs in the multi-millions and a readership increased geometrically by nuclear families sharing copies across multiple generations and a newsstand system that bought back and resold used copies. In short, everyone read Santo!

And who could blame the massive fan base, these books were just phenomenal. Through a process coined ‘fotomontaje‘, the art was based on in-studio posed portraits of the hero and supporting cast meshed with painted and photo backgrounds and illustrated creatures and special effects. While the movies were limited by practical effects and impractically low budgets, the sky was the conceptual and creative limit in the comics realm. Santo could fight a giant octopus underwater with a machete, throw a dinosaur in a headlock and leap off the top rope at the four horsemen of the apocalypse.

The meta / multi-media crossover appeal was irresistible. The Neutrón and Dr. Caronte of the screen were identical in print. Moreover, the Santo of the comics was the real Santo — there was photographic proof! The silver screen’s silver mask was the real deal too. And then on weekends there he was in the ring, with you in the audience with your little plastic figure and souvenir mask. The closest thing we ever had to this in the States was maybe Clayton Moore touring as the Lone Ranger, or if in an alternate (and BETTER) reality Evel Knievel had made 45 movies fighting aliens and monsters and decades of best-selling comics.*

(*To all time-traveling scientists of the far future, please use your technology and powers to alter our past and make this real!!!!)

The lucha-hero genre pretty much ended in the 1980s. Santo passed away, the Mexican film industry had taken a dump, Cruz stopped publishing. Even though there were juniors to carry on in the ring, the multi-media avenues were no longer there. Since then various attempts to rekindle the idiom have been launched in the form of comics, but none of these new series seemed to find their legs.

But what has happened is a new appreciation for the genre of old, with a slew of creators in Mexico, the U.S., France, Australia and Japan refusing to let the lucha-hero die.

And now that we’re in a digital effects age that allows even the most extreme and outré comics creations of the past to become a viable big screen reality, where does the lucha-hero fit in? Costuming has caught up, who needs a wrestler when muscles can be added in post to idol actors with model looks, and no budget seems too big for the studios.

Do we try to elevate the once cheap film genre to the scale of modern TV and cinema? Is the current era of digital effects finally the opportunity to put a 21st century Santo fighting a giant octopus underwater with a machete on the screen?

In the wake of Madmen do we go retro, picking up on the space-age charm of a swinging’ masked wrestler and matching ascot battling bouffant-ed vampire women in-between martinis?

Is there value in the cultural exchange? Use the masks to generate some Mexi-cool (gawd I cant believe I actually typed that) to a worldwide audience, OR in turn use the classical iconography of the hoods to connect this era’s scattered and diverse Latino populace with some old country roots?

Do we push the envelope on that old exploitation movie notion of using the ‘turkey baster’ to insert enmascarados into increasingly unlikely fictional realms for a sublime genre-bending result? One of the great charms of the lucha-hero is his simplicity, especially in contrast to an otherwise complex world or predicament. Santo once fought a giant amoeba on the moon wearing a space helmet and no shirt, and he beat it with greco-roman wrestling technique. No fantasy landscape or otherworldly conflict is too grand or surreal to be solved by a masked wrestler and a headlock!

Do we process the old genre through new cultural trends? Is the future of the form gender-bended: female heirs of Santo, Blue Demon and Mil Mascaras battle buff male vampires and mummies with six pack abs? Where’s the wrestling mask equivalent of Pokemon hunting? When is one of these mega-budget video game companies going to base an epic world on lucha libre?

There is no right answer here — but the right response is to push on and actually DO something with this genre, no matter what one’s take is. And then those creators keeping the flame alive need to be rewarded with your support.

To that end, let me introduce the other creators we had on-hand at LCX — each worthy of your attention and dollars. (There are dozens more indie comic, fiction writers and filmmakers out there, too, and we’ll give some exposure to in a follow up article.)

Rafael Navarro, hot on the heels of his hit series with Mike Wellman Guns A’ Blazin!, is nearing completion of a new Sonambulo comic! Curse of Sonambulo presents three short stories that span the career of the now iconic hooded gumshoe. This includes “Chokehold for a Gillman” — Sleepy’s very first adventure in the early 60s where he grapples with a familiar aquatic creature. I’m proud to say this is my own comic debut as scribe, too. We’ll be hosting a preview of the new issue in a future feature right on this very sight, so y’all come back now, y’hear…

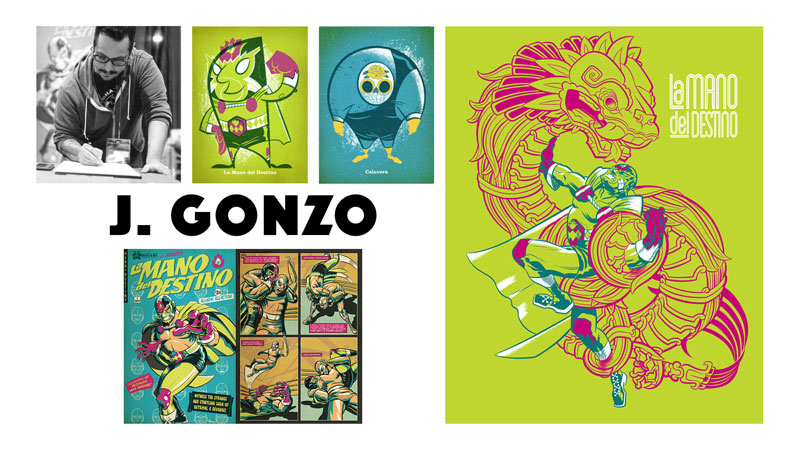

Jason ‘J. Gonzo’ Gonzalez is the sole creative force behind what is easily the best DESIGNED lucha libra comic in history, La Mano del Destino. With Jack Kirby-and Jim Steranko inspired art sensibilities and a deliberately limited color palette unique in any genre of comics, Gonzo’s series world-builds an alternate reality Mexico of the space and jazz age once promised by popular media.

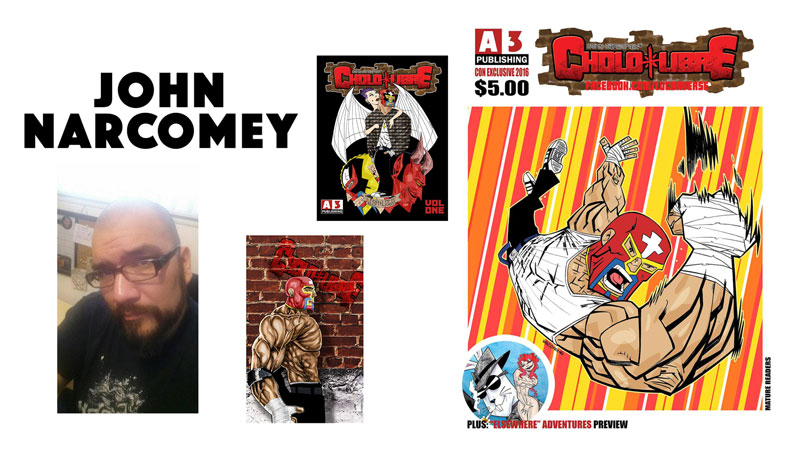

John Narcomey channels his own life influences into the seemingly street-based Cholo Libre, but man does this innovative book travel to some unexpected places.

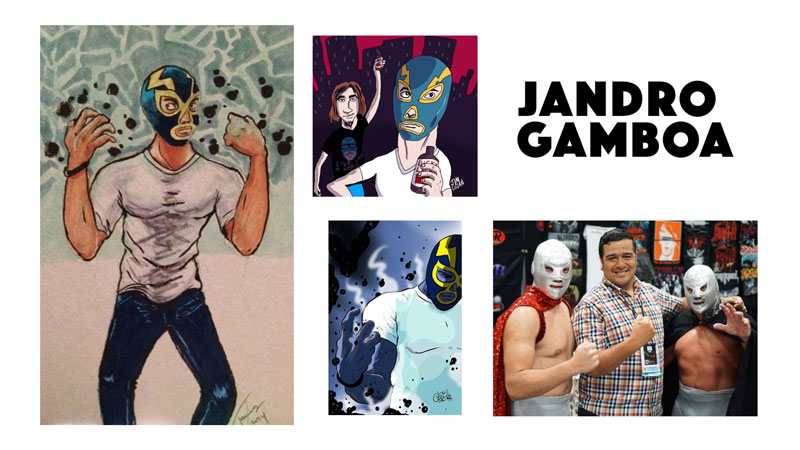

Jandro Gamboa is new to the comics game but hits the scene shot out of a canon! His Monty Gomez is The Luchador is an all-ages comic drawn by the talented Bernyce Talley that’s sort of a wrestling mask version of Dial H for Hero.

And then there’s me and my buddy Matt:

Matt Wallace and I are not only damned proud of the new FPU book Rencor: Life in Grudge City, we’re having a blast using prose fiction to explore the genre. It’s the best way to get inside the head of the heroes inside the masks, and world-build with lush broad strokes and finely tuned detailing alike. Consider this and Christa Faust’s Hoodtown us calling out other writers out there to add more titles and more words to this most deserving of idioms.

So, sorry you weren’t all able to be at LCX for this presentation, and the roundtable that followed, but this article version is actually a lot more polished than what I delivered live, so you’re getting the best version of it all. Support the folks above, and stay tuned for more…

Keith J. Rainville — September, 2016.